Flexible nibs (which I did an earlier post about here) are often coveted but just as often misunderstood by fountain pen collectors. That’s to be expected since nearly all current pens have nibs that flex very little. If not stiff then they are what is often called “soft”, a term that means under some pressure the tines will spread a tiny bit.

Idolatry

So why are flex nibs so coveted and how do you get one? People can get sold on them sight unseen due to all the dialogue praising them but don’t know of the downside. Most new owners would find them hard to use on a daily basis. You have to take your time writing with one and the necessary high ink flow means a lot of drying time which leads to disappointment and some grumbling you don’t often see expressed due to embarrassment. If given a little perseverance (and practice) most folks do come to enjoy their use.

Getting the real McCoy usually involves finding a good vintage pen from the golden era of flexibility which ended in the late 1930s. It’s a hard quest since so many people selling “flexible” nib pens have no idea what that adjective really means in those cases. Thus caveat emptor needs to be strongly observed so you don’t wind up holding a nail when you wanted a noodle. Trying out pens in person or buying from a known, recommended, or trusted seller is really a very, very good idea.

Into the 21st Century

The other way to obtain a flexible nib also can be tricky. Some very high end manufactures have special order flexy ones and some nibmeisters can alter what you have on hand to be such for a hefty price. People debate the qualities of these all the time asking if they are truly flexible or just rigid with a lazy streak. Results do indeed vary.

Now Into this comes a new much talked about entry from Noodler’s, the people well known for ink and low cost fountain pens. The Nib Creaper (or NC since I’m lazy) is billed to have a flexible nib on a very low cost pen. Intriguing, yes? Well I’ve managed to get my hands on a couple through the auspices of kind friends and took some time to get to know it. Let’s take a look.

The Same, But Different

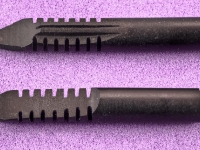

Do you like the look of the exsisting Noodler’s piston fill fountain pens (as shown here)? If you do then you’ll like the Nib Creeper. I don’t find the design unattractive or all that attractive. It’s a nice generic pen shape with little adornment. There’s nothing wrong with that, as I said before, since it’s an inexpensive pen. For this price point you don’t expect too much and just the fact this is a piston filled pen is a nice surprise.

This is one of the cheapest new piston filling fountain pen I can think of. The Dollar Pen rivals it for price but I’ve had no experience with them so I can’t comment on quality. Oh, and the Dollar does not have a fancy nib. The TWISBI piston filler is a fine pen and built to a much higher level of quality but it goes for nearly 4 times the price of the Nib Creaper. If someone wants to get away from converters or cartridges first stop is here.

How long a Noodler’s pen such as this will last in use is an open question. It looks to me built to perform a good long time and you can buy new piston seals from Noodler’s to replace worn ones (a nice touch.) The design is straight forward and simple much like the “school pens” from European manufacturers in the 50s and 60s. You see the minimum of parts to get the job done on this pen so rough handling should not break it.

The Exciting Bit

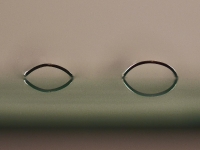

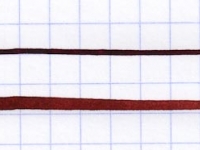

Now that we’ve discussed the supporting cast let us get to the star of this pen: The new flexible nib. If you look at the overhead comparison shot between a regular Noodler’s and the NC’s steel nib you immediately see the difference. The slit on the normal nib is goes part way up and ends in a breather hole. No surprise there since it’s the classic nib look and the one people visualize when thinking of one.

Now look at the nib next door. Wow! The NC’s slit travels much farther up the nib and does not have a breather hole. Why is that? Well you can also see that both nibs are about the same thickness and (I assume) made from similar steel. Flexible nibs from the past were made thinner and some say from a different alloy of gold to make them springier. If you can’t do that kind of engineering then the long slit is a path to flex on the cheap. Here the two nib tines have more freedom to move since they are effectively longer and of less width than a common nib. Visualize this by thinking of an index card being cut along its length: If the cut is an inch into it and you push up on one side it moves a little but if the cut is 3 times that long you’ll have something a lot floppier.

What about the vent hole you ask? Well, what about it? The purpose of one is supposedly to allow air to flow in to replace the outgoing ink more efficiently. However a lot pens have done without it and seem to have no ill effects. Additionally with a slit that goes up to where everything snugs into the section it makes little sense on the NC to have one.

The Unseen Hero

One thing about flex nibs that people should know about is that they need a lot of ink. When they are flexed to make a thick line they have to put down a wide swath of that liquid stuff and if there’s not enough ink coming up through the feed they “railroad”. That means each tine makes a thin line and there is a blank nothingness between them. That is bad. Now if there is enough ink to cover that gap you see a very wet line indeed. The balance between too much and too little ink is usually in major part controlled by the feed of the pen. Of course I should mention there is always a point where railroading will happen if a nib is flexed really far and capillary attraction loses out to gravity and other forces.

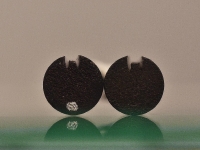

Flexy pen feeds that work well have deep channels holding ample ink ready to be called upon when needed. In the picture below I’ve taken a few photos of the regular Noodler’s piston fill feed and the one from the NC. I love that these are great looking old school ebonite feeds since it’s nice to see something made today that looks just like it’s counterpart from 100 years past. No molded plastic fanciness here, just good old lathed hard rubber.

You can see that the feed for the flex nib pen is more robust in construction especially along the bottom where material was added. Perhaps the idea was these new pens will get more of a workout and so this part was beefed up to prevent breakage? The other change is the very important use of larger feed channels to supply more ink. Seeing this shows that the pen isn’t just a “swap the nib” endeavor but there is thought behind it.

In summary we see that that the Nib Creaper has a new nib and feed on the same barrel as the regular Noodler’s piston fill pen. Well, there is one cool additional difference: The colors (or lack thereof.) Initially the NC was introduced in black mottled red and clear demonstrator plastic but at the time of this writing a black mottled white pen is being sold too. The swirled colors are a welcome and interesting visual change from the solid ones. As for the demonstrator, who doesn’t love those? (If you don’t please just slink out of the room now.)

So, What About That Flex?

We all know the real question everyone wants answered about this pen is how flexible is the nib really? Using it gives an impression but that is subjective and hard to relate in words. One person’s flexible nib is another’s rock hard nail like scratching device.

What I had to figure out was how to test and show the Creaper’s flexnibedness. A comparison between a vintage pen I think anyone would describe as having a flexible nib and this modern upstart made sense. Looking for a good wet noodle as a comparator I was lucky to have a vintage model also sporting a steel nib (even better for the comparison) on hand. This flag bearer for flex is a 50s Montblanc that can accelerate from narrow line to wide in the wink of an eye. Once that choice was made I moved forward to formulate a hair brained scheme.

What I needed was a way to illustrate how much flex there was using the same downward writing pressure on both pens. After a great deal (practically minutes) of thought I came up with two options which could work. In the first one I would buy expensive equipment to apply the exact same measured force to both pens and run a moving belt of paper underneath to capture the lines. Then I use magnification and a micrometer to measure the line width to high accuracy.

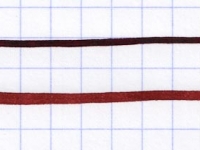

Yeah, right. I’m lazy and all for loose, unscientific tests that don’t cost me anything so I selected the second path: duck tape. Since it can do anything I figured it would provide me a cheap and cheerful testing solution. So what I did was tape both pens together with the points at an equal level to each other and on the same plane.. With that done I made lines across the paper increasing the pressure as I went. Since the pens are, so to say, a single unit the pressure was pretty equal on both.

The results in the scans above (you’ll want to click on the images to see it all) show a couple things: Yes, the Noodler’s Nib Creaper will flex. No, it doesn’t flex as easily as a vintage nib does.

So, How Is It to Use?

My use bears out what the duck tape experirama shows in that the Noodler’s pen was not an entirely willing flexible partner. It takes a good deal of pressure to get line variation and that makes it a bit less enjoyable.

The next issue is that both nibs I tried were a bit scratchy. I’ve read some people’s reviews where they state the pen was very smooth so this may just be an anomaly or maybe I am a tougher judge of smoothness. As always this is something you will have to see for yourself.

My last comment has to do with ink supply. Even with the modified feed the pen railroads quite a bit. To stop this you can write slowly and deliberately which slows the rate of ink being put on paper so the flow can keep up. This is something some flexible nib pens require but it can be a bit exasperating.

Everything I said in my review of the normal Noodler’s piston filled pen goes for this one. It’s a featherweight pen which makes the NC easy to use and carry. The piston works as advertised and there are convenient ink windows in the barrel to see the level of such. On top of all this is a screw cap which is my favorite method of holding one on.

Whadda I Think?

A fountain pen that is this inexpensive makes me want to play up the positives and minimize the negatives. You get good value for your money with a Noodler’s Nib Creaper for sure but as with all things you do get what you pay for. That turns out to be a fun pen to use but not an amazing wet-noodle nib writing experience. For that your best bet still is going for a vintage pen.